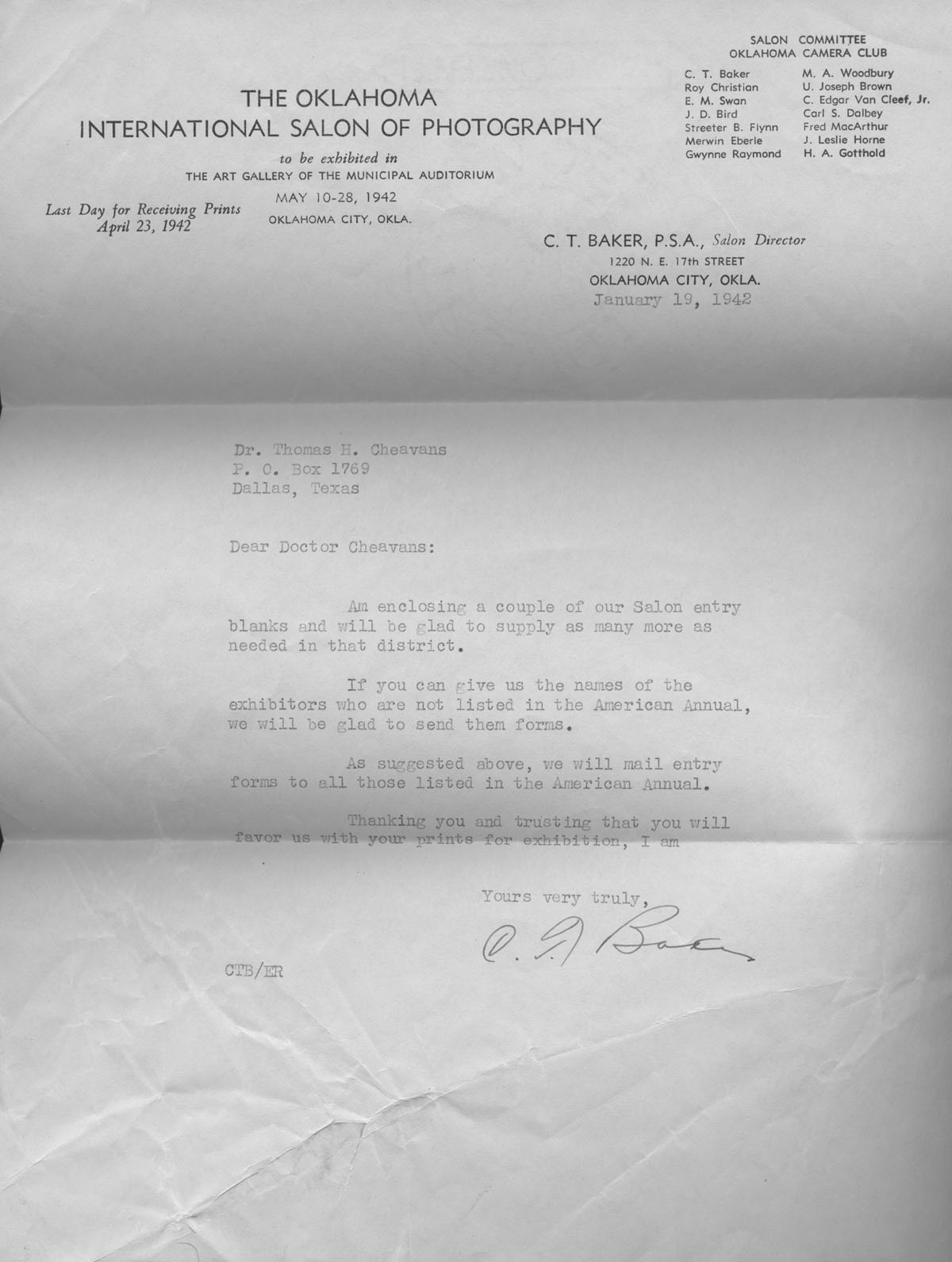

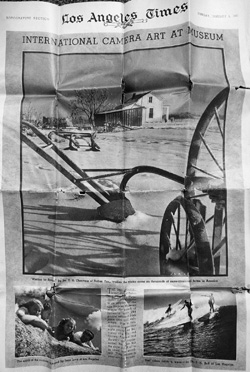

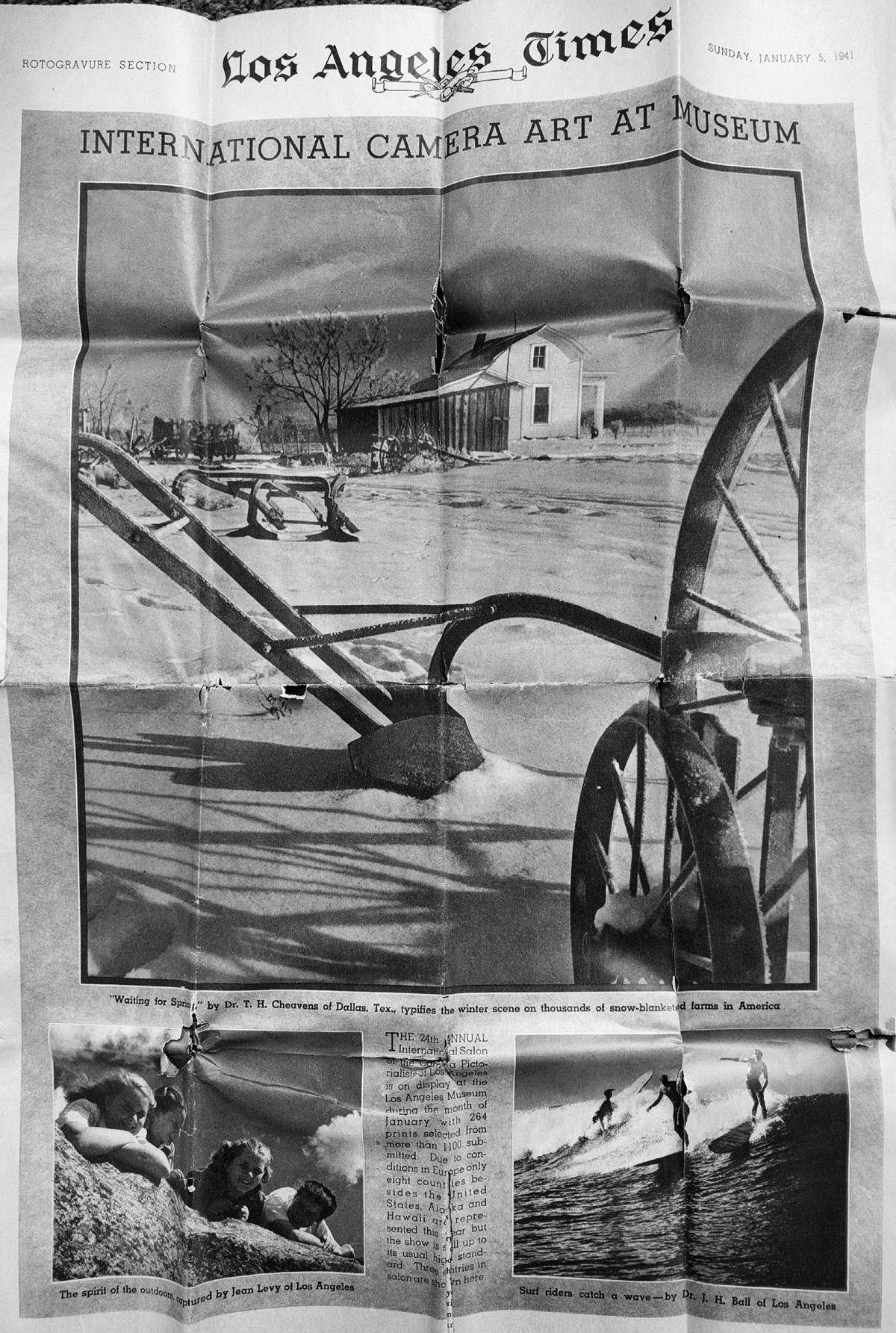

T.H. Cheavens, MD (1903-1943)

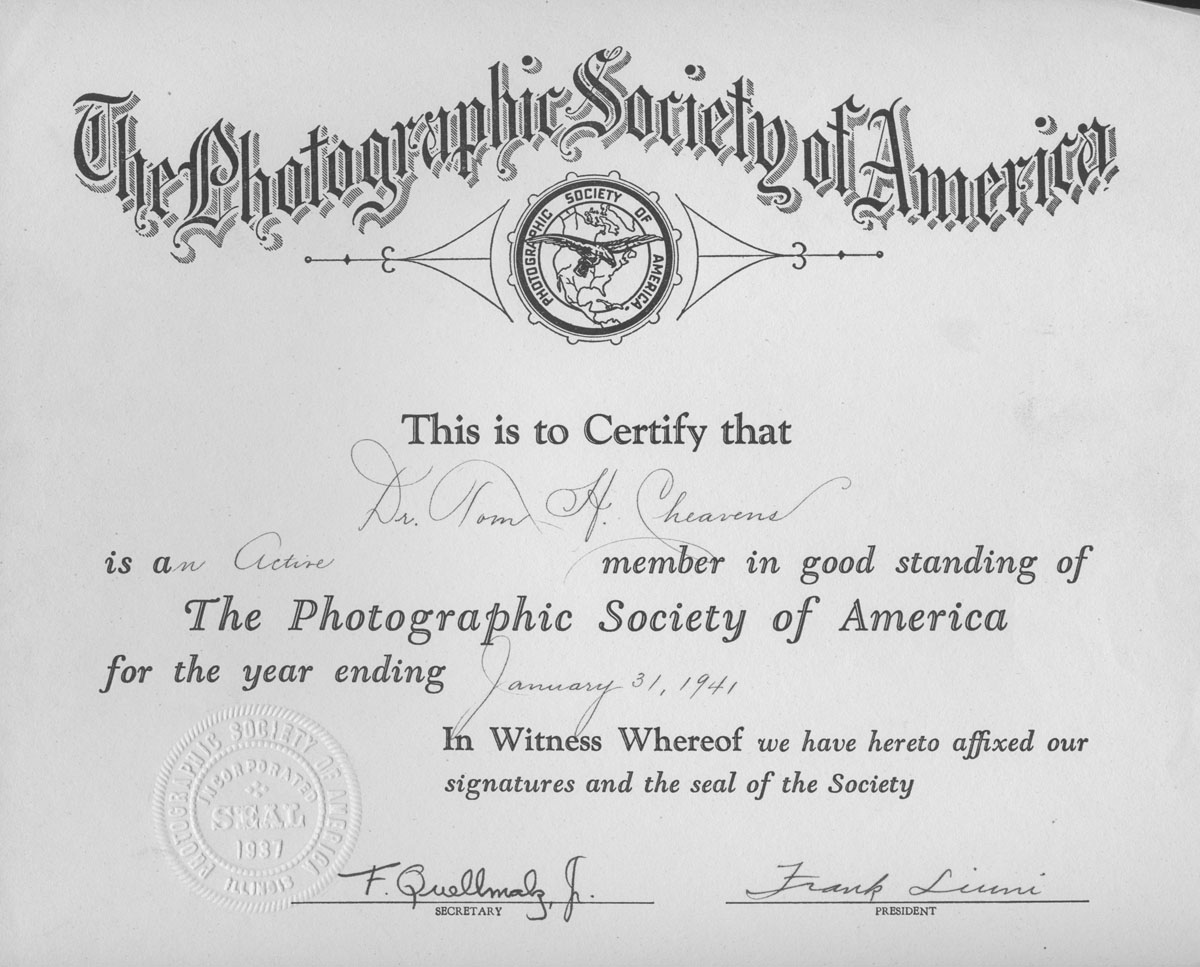

Thomas Henry Cheavens was born on July 19, 1903 in Saltillo, Mexico. His father, John Self Cheavens, was a Baptist missionary and founder of the National Baptist Convention of Mexico. One of seven children, Tom grew up in the borderlands between Mexico and the United States, living in Saltillo and Torreon and later in Eagle Pass and El Paso when the Mexican Revolution made missionary work too hazardous. He graduated from high school in El Paso and enrolled at Baylor University and Baylor College of Medicine. While at Baylor, he served as business manager of the Baylor Lariat newspaper. He was also the chief yell leader and author of the “Long Yell” known still to every Baylor sports fan. Paying for his own education, he also worked as a carpenter’s helper, dishwasher, advertising salesman, nurse and information clerk at Baylor Hospital. Somewhere in between, he found time to meet and marry Sarah Newsom of Coleman, Texas.

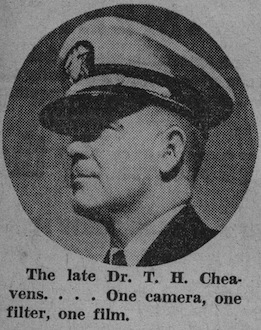

Upon graduation from Baylor College of Medicine in 1928, Tom did post-graduate work in Denver and New York City before moving to Dallas Texas where he began practicing psychiatry, joining Dr. George E. Witt at Timberlawn Sanitarium, the first private residential psychiatry hospital west of the Mississippi River. While there, he wrote and co-wrote several medical papers, including one for the Southern Medical Journal titled “Prolonged Barbiturate Narcosis in Acute Psychoses” about using sleep-inducing drugs to produce a “prolonged flight from reality…” He also served as assistant professor of clinical neuropsychiatry at Baylor College of Medicine. He bought his first house near Timberlawn and began raising a family that ultimately included three children, son Tom and daughters Ann and Carol.

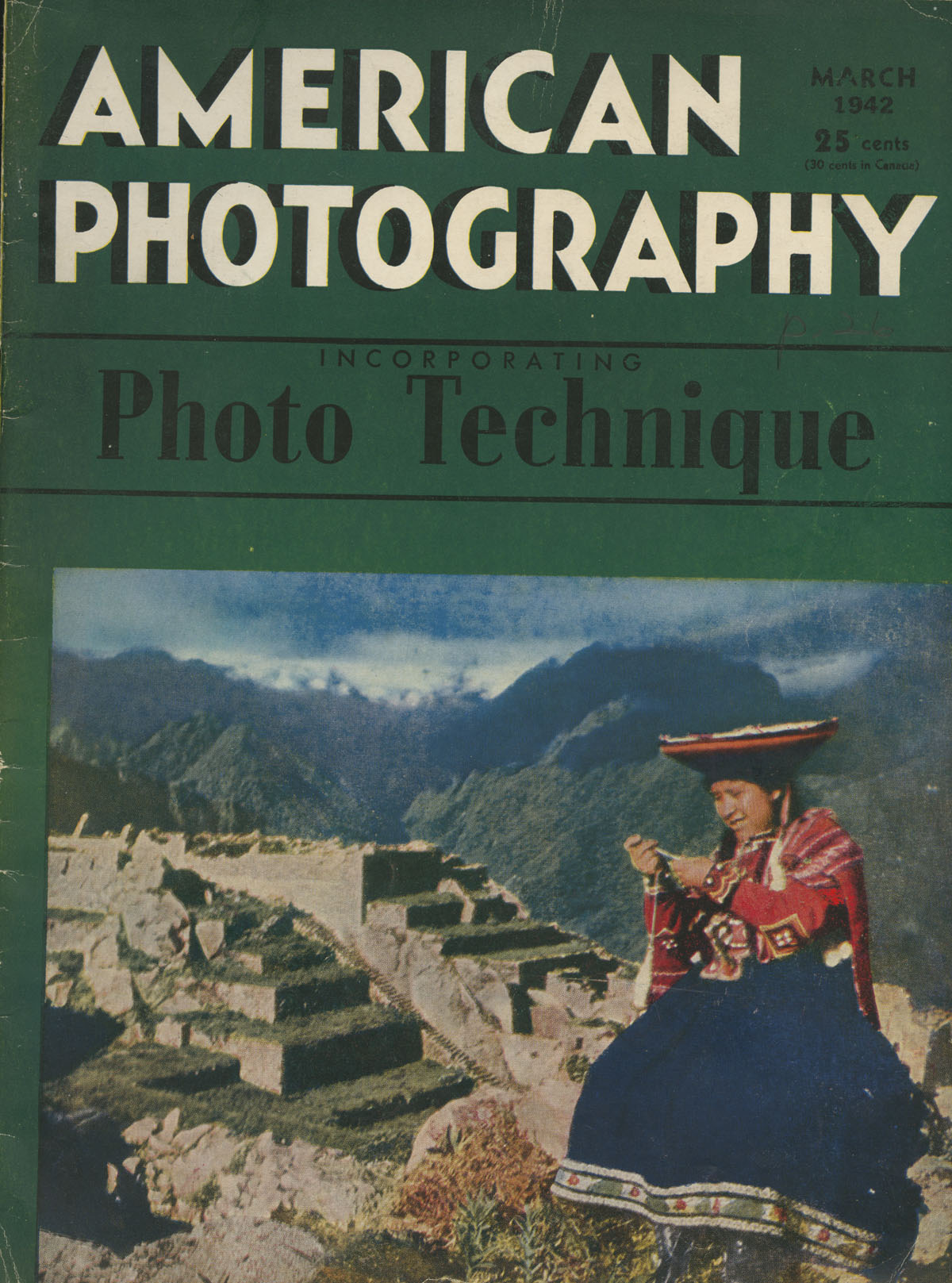

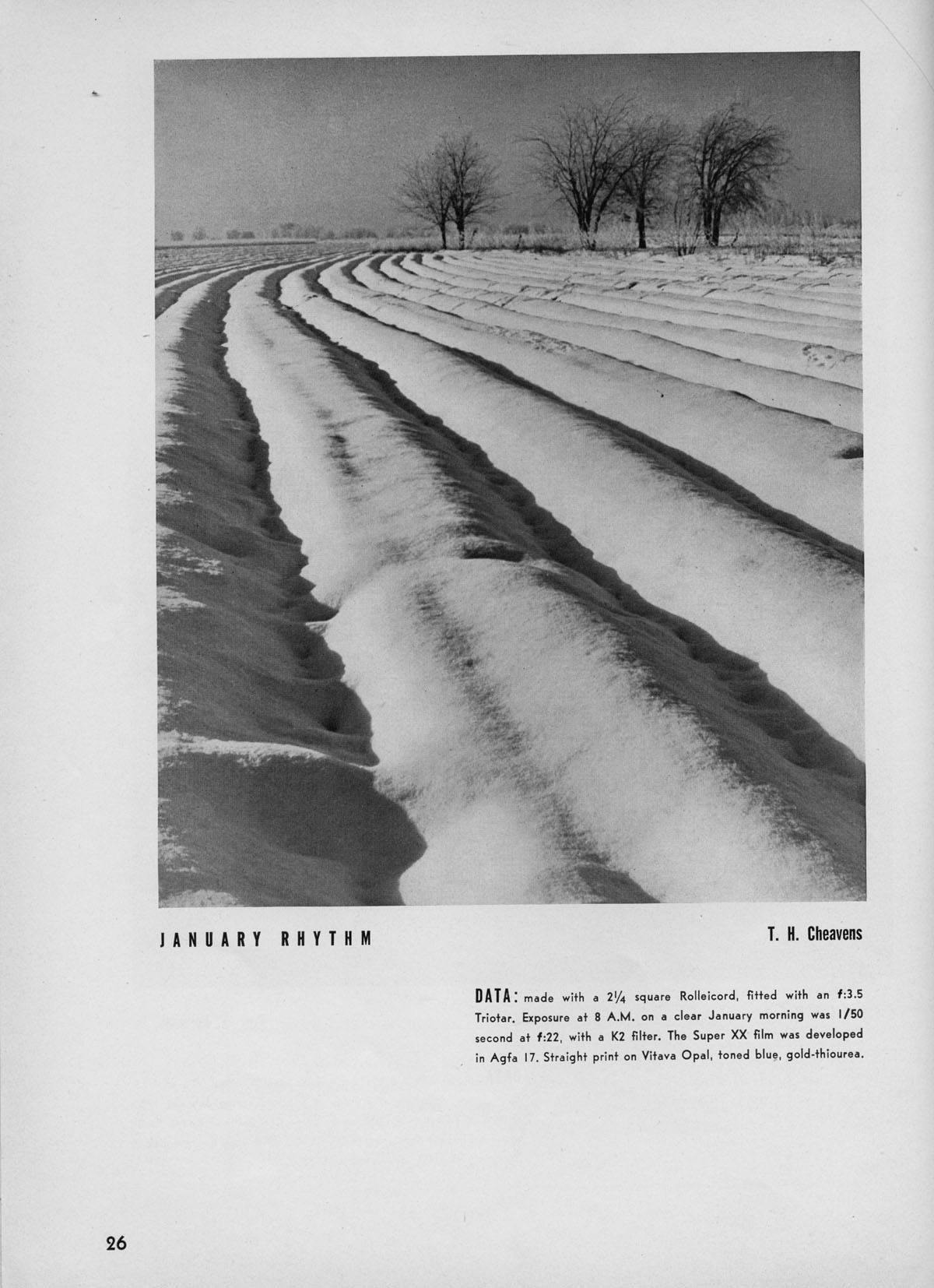

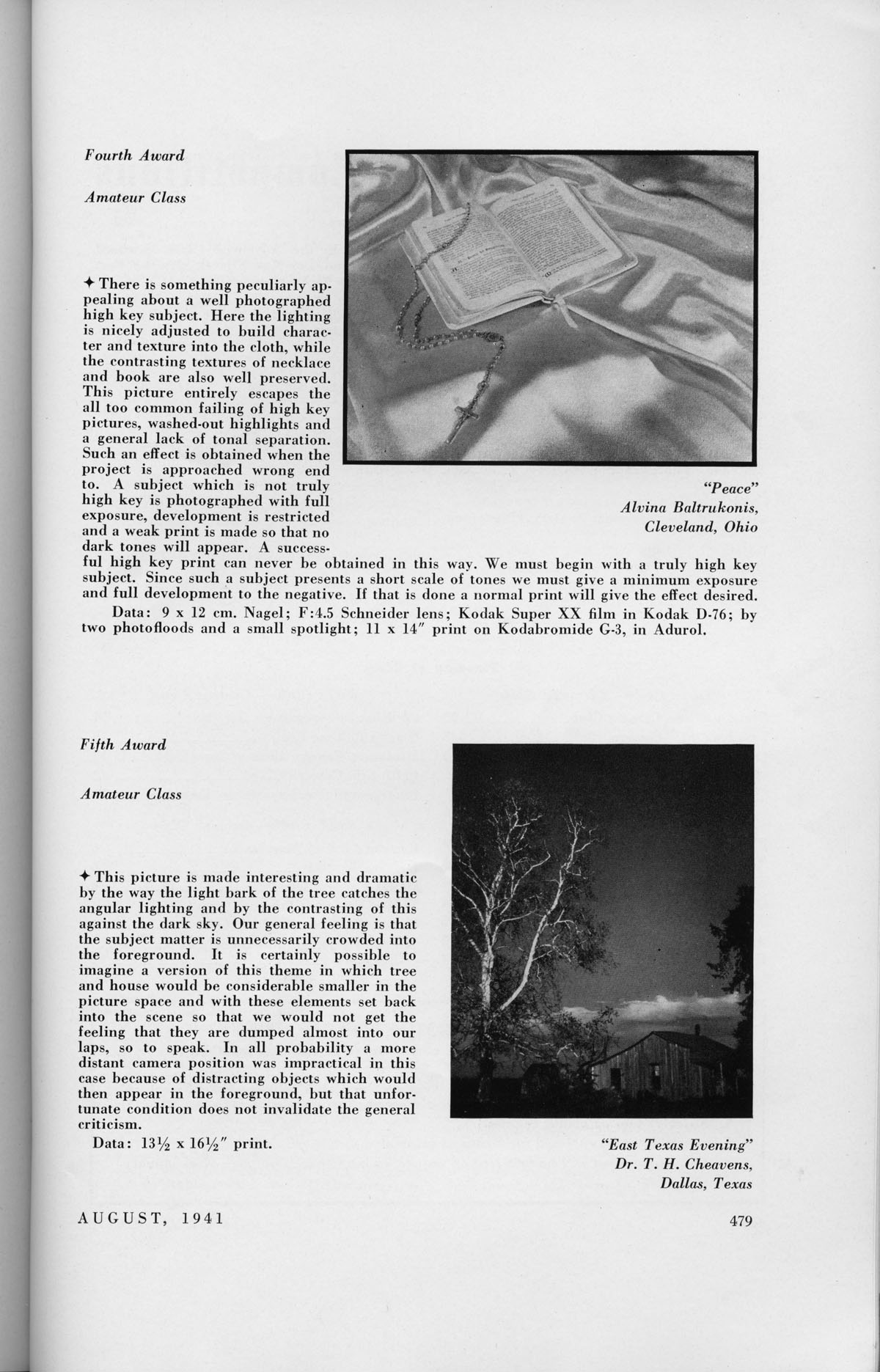

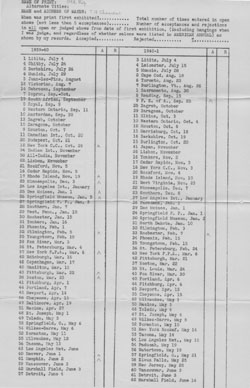

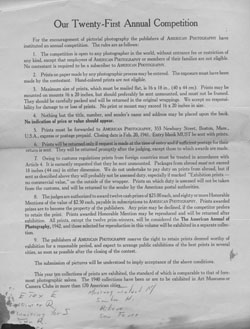

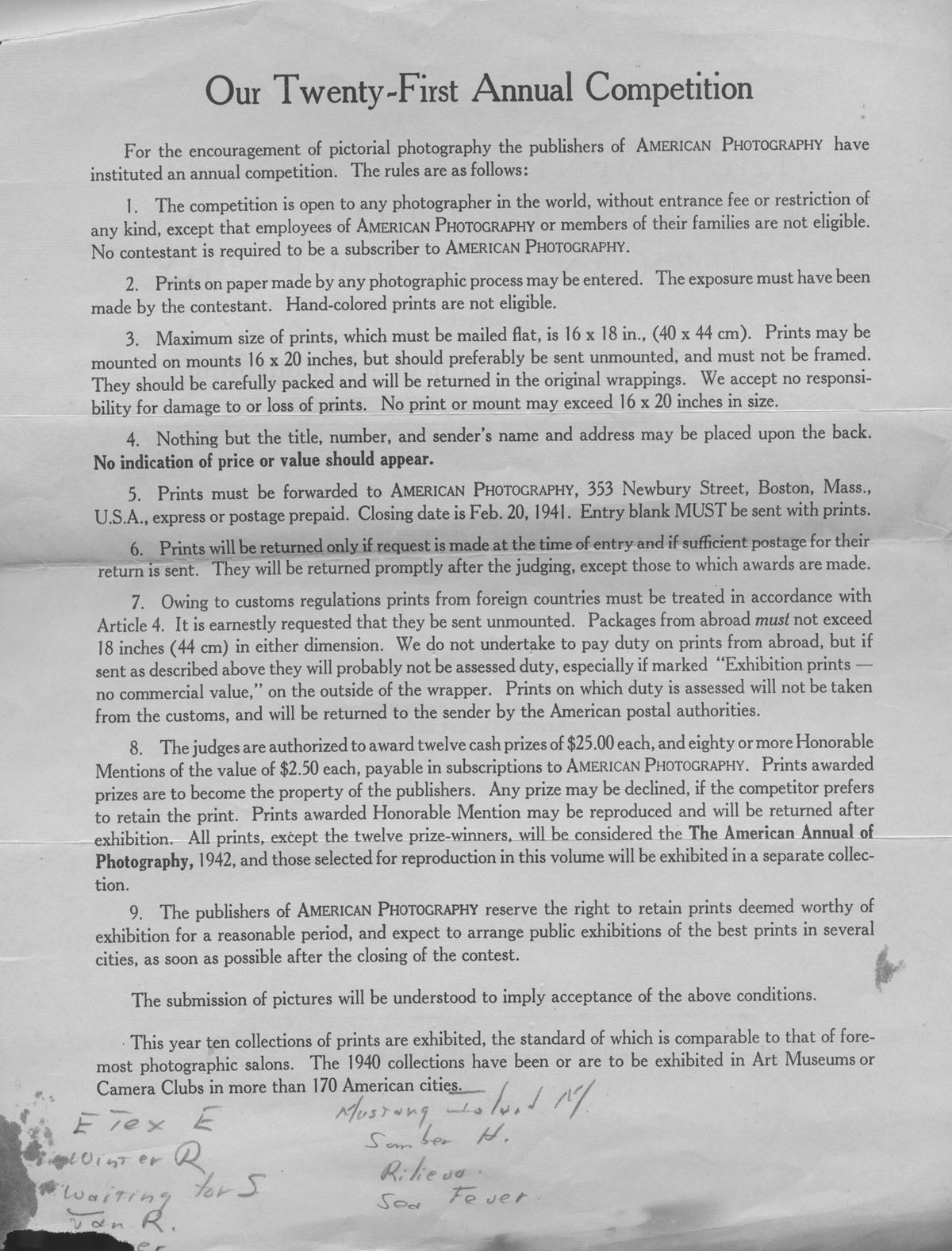

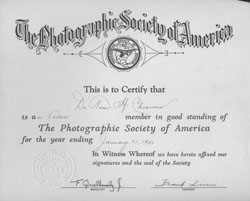

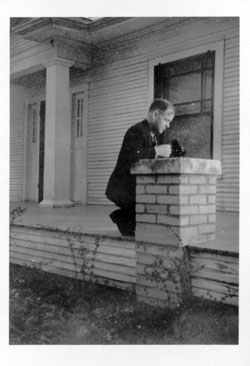

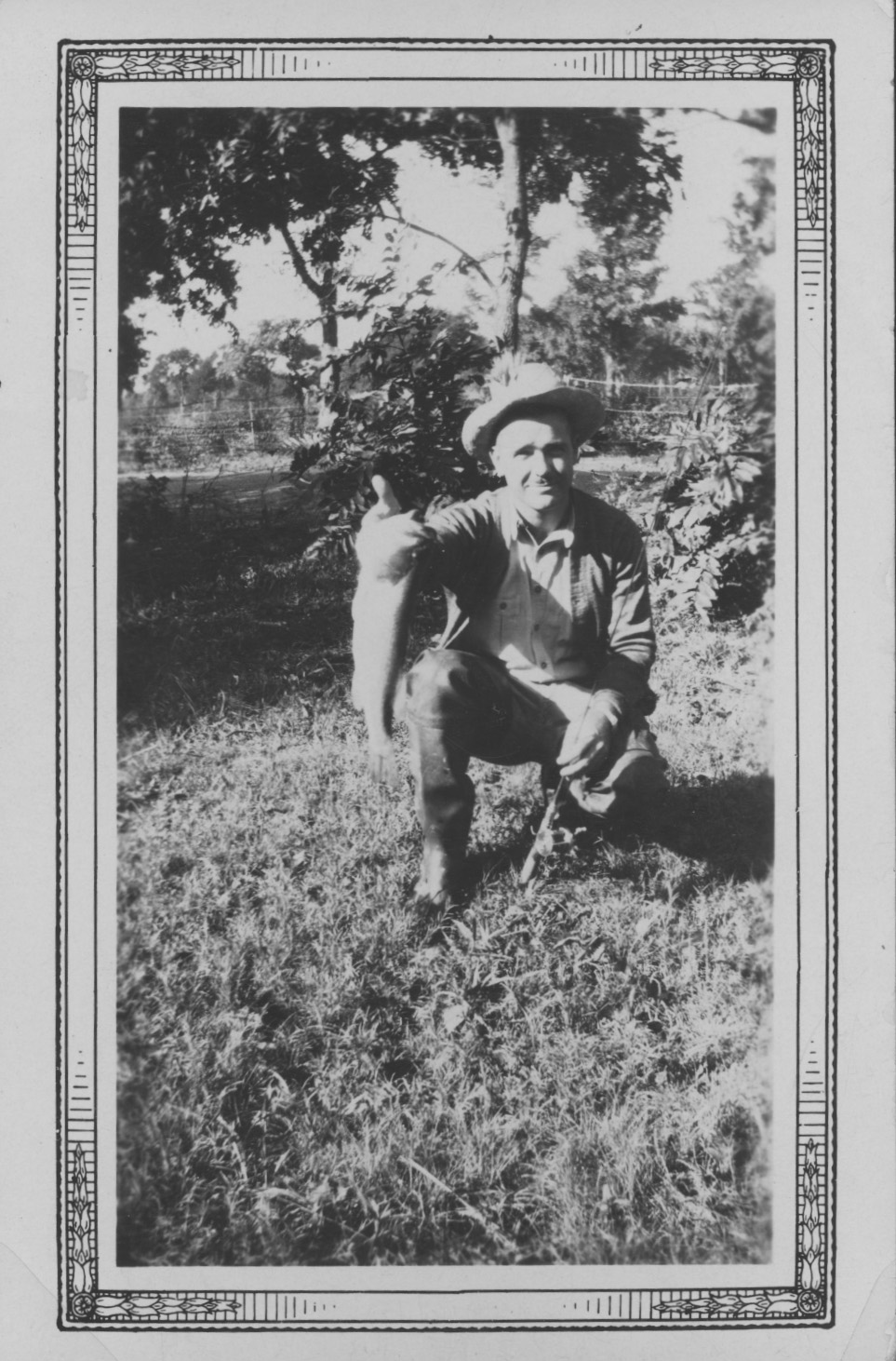

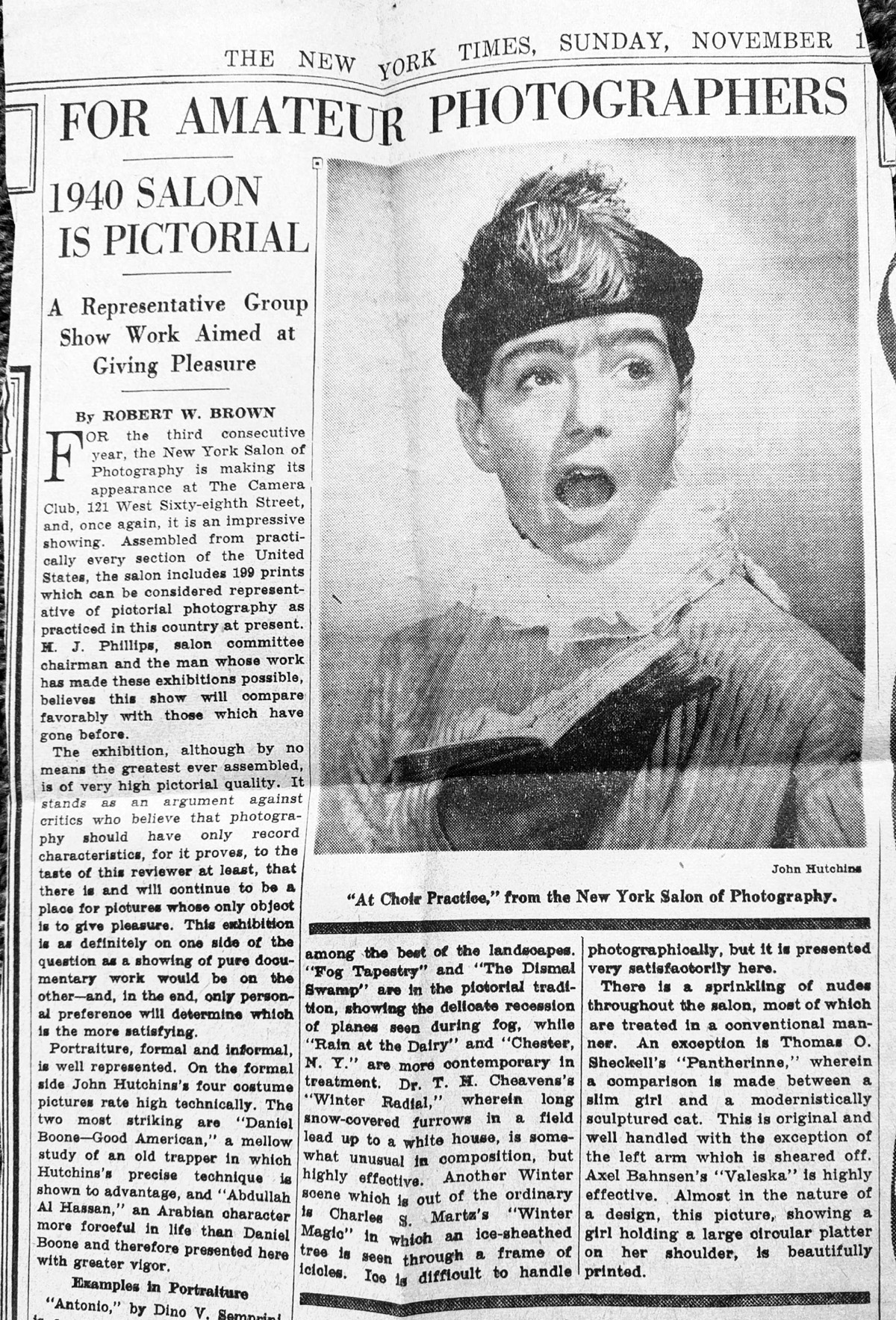

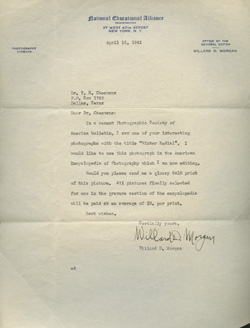

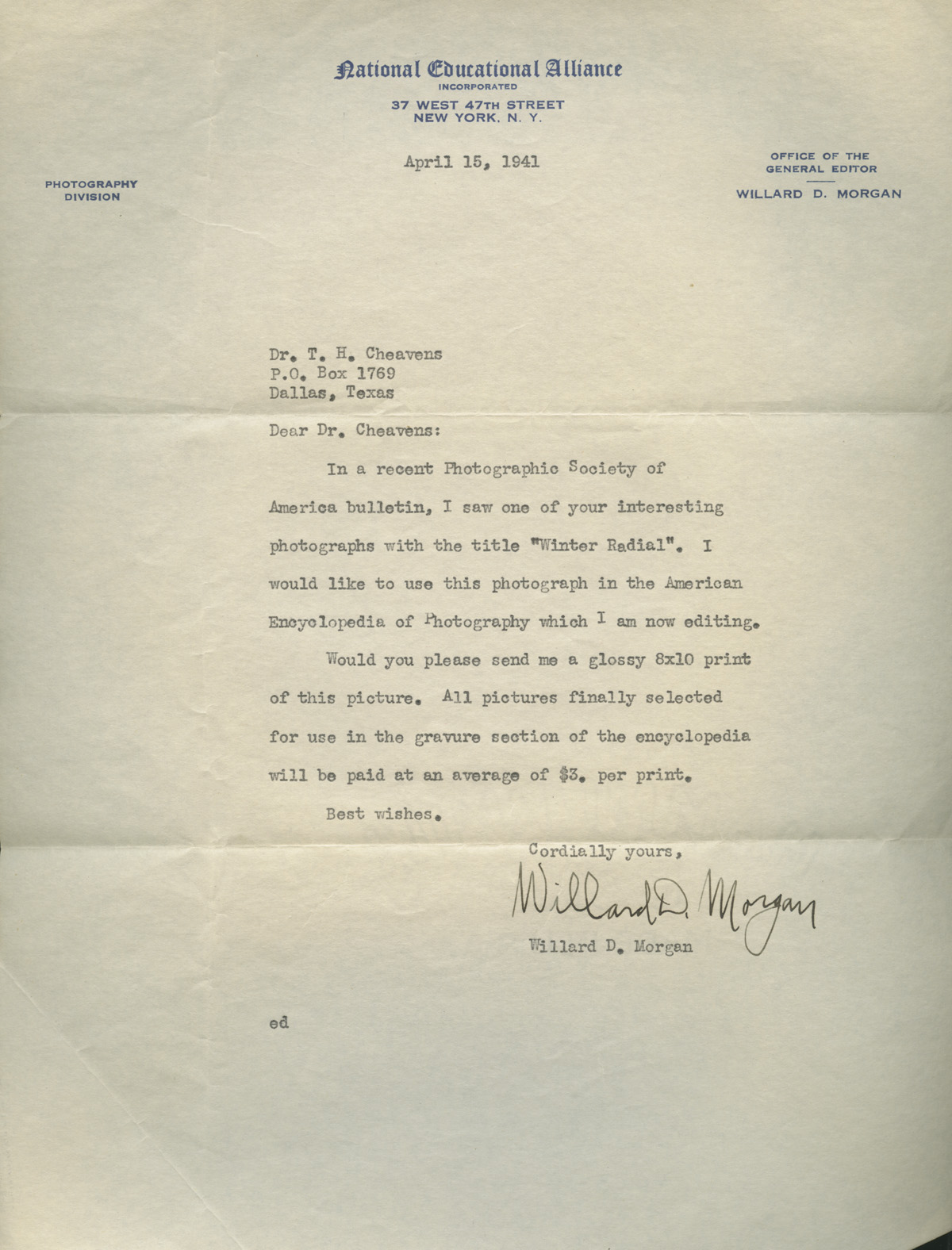

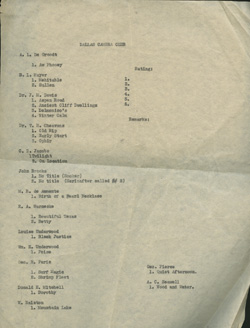

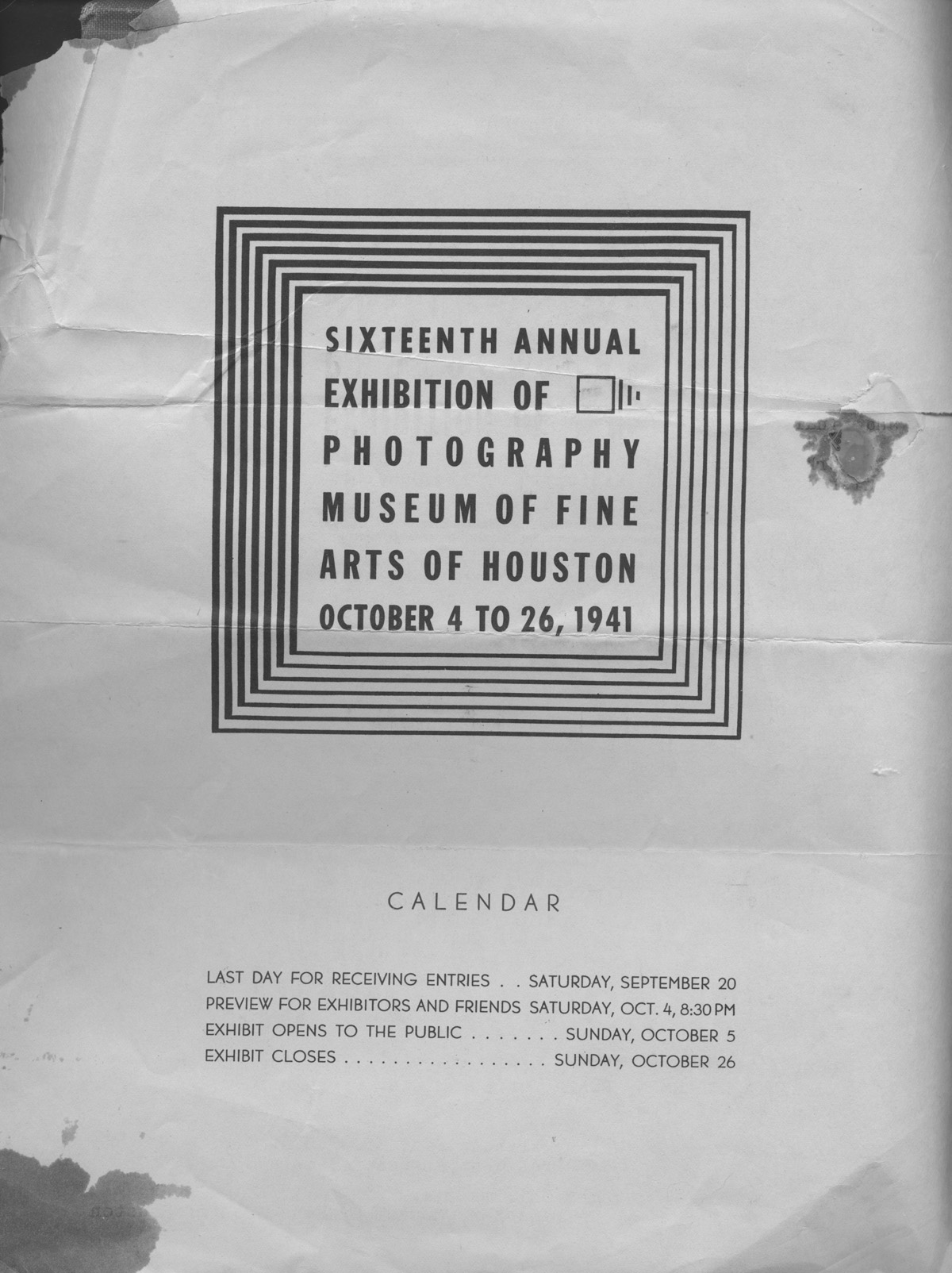

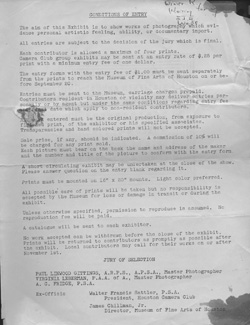

In 1938, Cheavens became interested in photography. He purchased a Rolleicord rangefinder camera and began taking pictures wherever he went, mostly in Texas but a few as far afield as Cincinnati and Chicago. Some of his favorite places to photograph were in and around Athens, Caddo Lake, Port Aransas, Coleman and Plainview. While he became known for his landscape photography, Cheavens also photographed the rural working poor, often at their jobs plowing fields, sawing lumber, fishing and shrimping. Because he was an early and passionate adopter of the fly rod, many of his photographs were taken during fishing expeditions in East Texas.

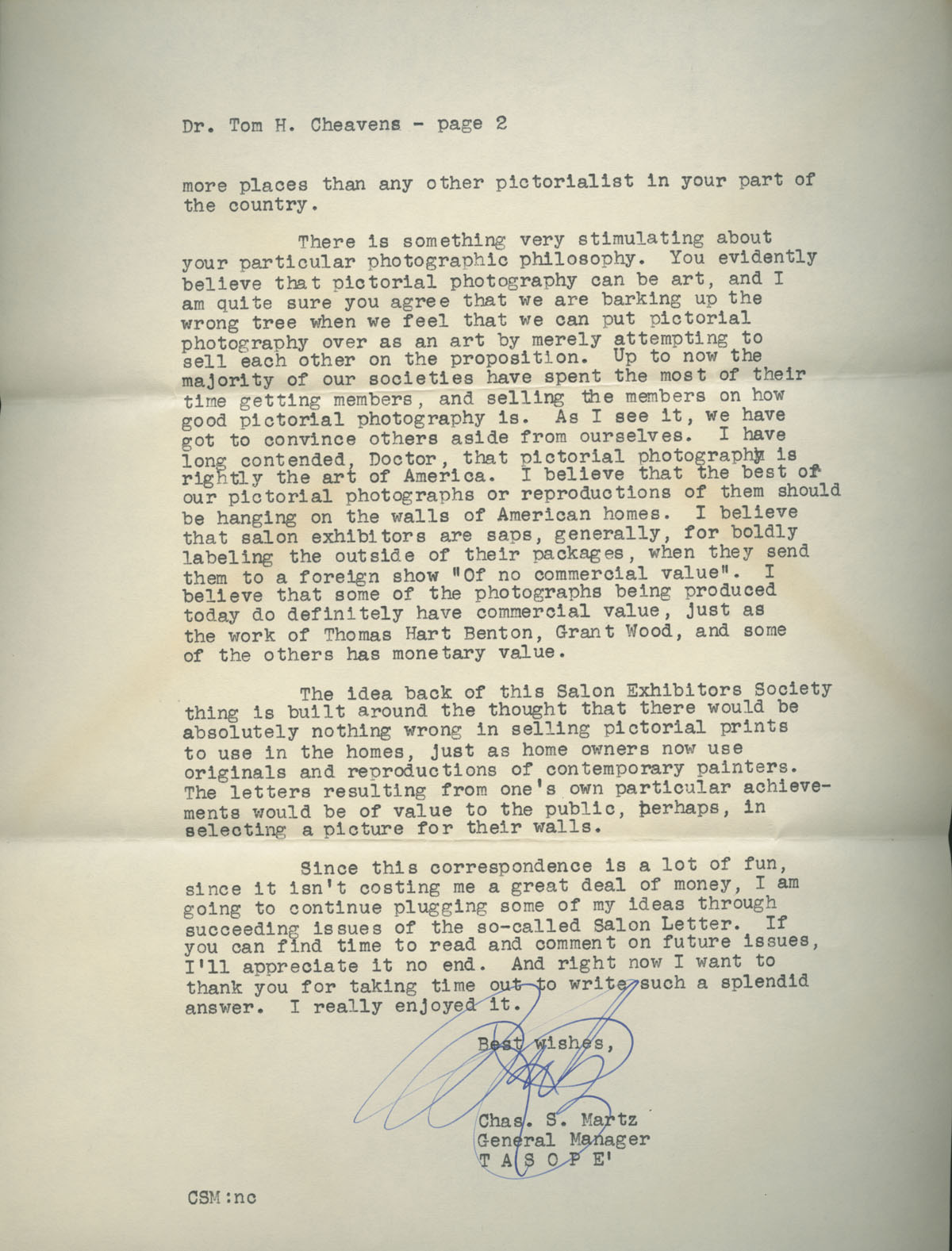

In April of 1942, Cheavens joined the Navy Medical Corps as a lieutenant commander and was assigned to duty at the Naval Medical Center in San Diego, treating soldiers returning from the Pacific Theatre. He put down his camera, took a leave of absence from Timberlawn and moved his family to California. On February 23, 1943, at the age of 39, while on duty at the hospital, he contracted pneumonia and died.

Before he moved to San Diego and put his photography on hold, Cheavens had created almost 2,300 negatives, the vast majority with his Rolleicord but many also with a large format Graflex camera. Although the exact number of prints made from these negatives and shown at salons and elsewhere is unknown, there were twenty-one photographs that were exhibited posthumously at the Dallas Museum of Art in 1943. The vast majority of the remaining unprinted negatives were relegated to two shoeboxes in Sarah Cheavens's attic where they remained untouched until her death in 1989.

After rescuing the negatives from a near-death experience with a cleaning company trash can and a darkroom chemical spill, his grandson, Brad Moody, began building a catalogue and making the prints that his grandfather couldn’t because of time and tragic circumstance. The images on this website are the result of Moody's effort to resurrect his grandfather’s work and to give everyone a glimpse both of the photographer that Tom Cheavens was before the war and perhaps also the photographer that he would have been had his life not been cut short. Texas and Texans are too big and too diverse to be captured by any one photographer but with his gifted eye for light and contrast and careful composition, Cheavens portrayed his state and its people with honesty, compassion and a quiet sense of simple majesty that stands in stark contrast to the stereotyped Texas of today.

|

|

|

Artist's Statement

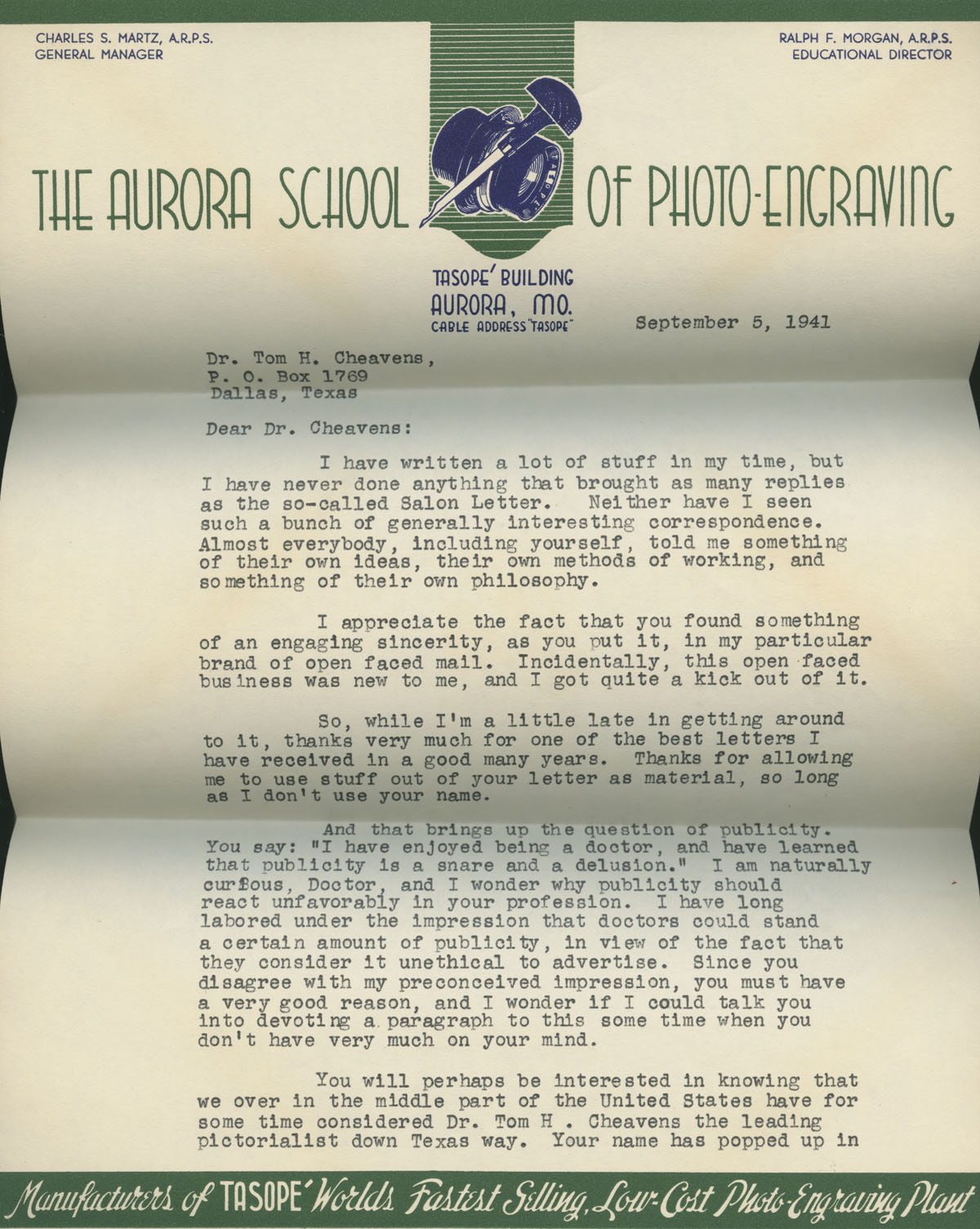

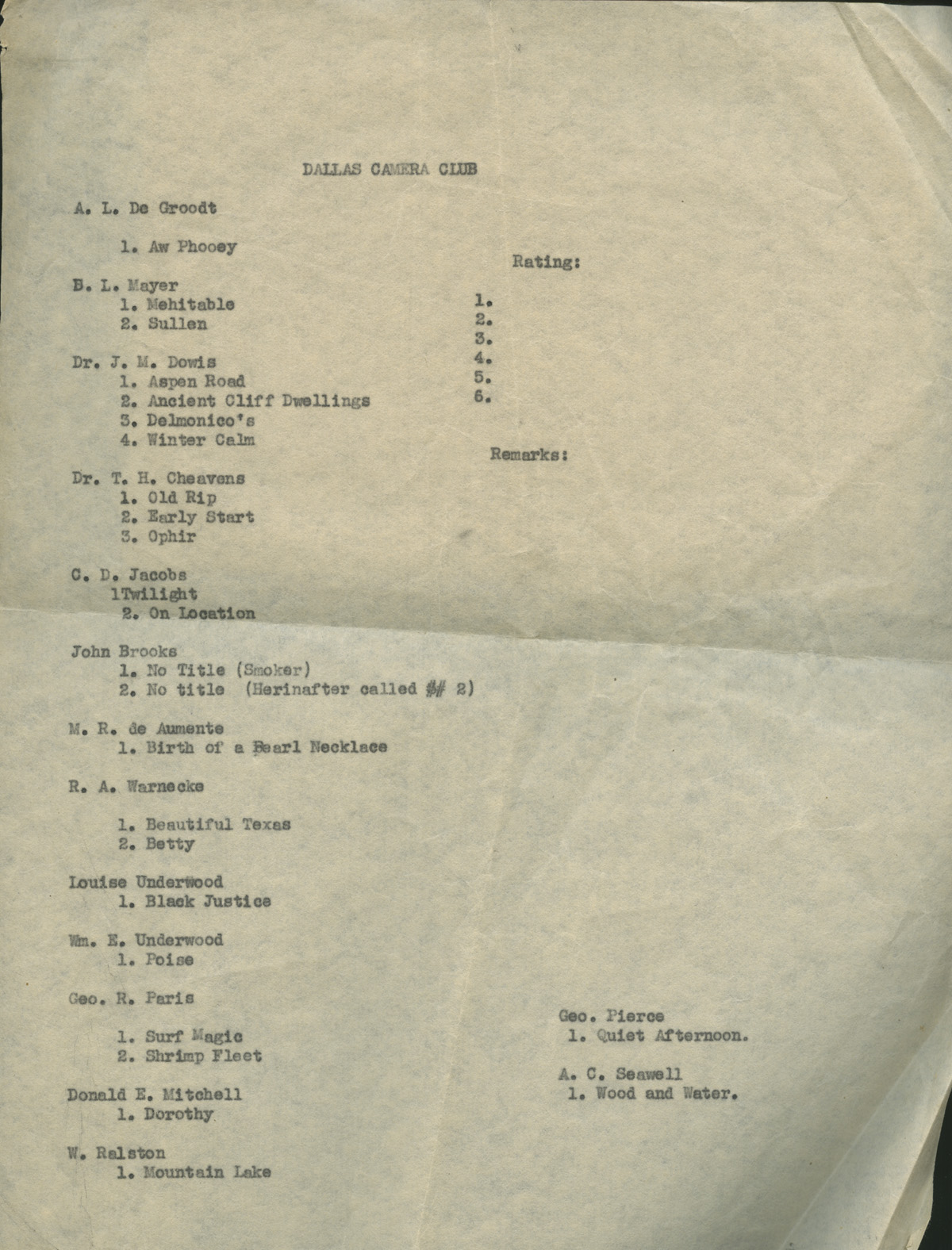

c. 1939I am now completing my second year in active amateur photography. During this period I have taken pictures steadily. I have kept up with the current photographic literature reasonably well, wherever and whenever I could. I have looked at pictures my friends’ Sunday afternoon snapshots, the monthly competitions in the camera club, window displays in camera stores, advertisements, illustrations, salons, and reproductions in the photographic magazines and annuals.

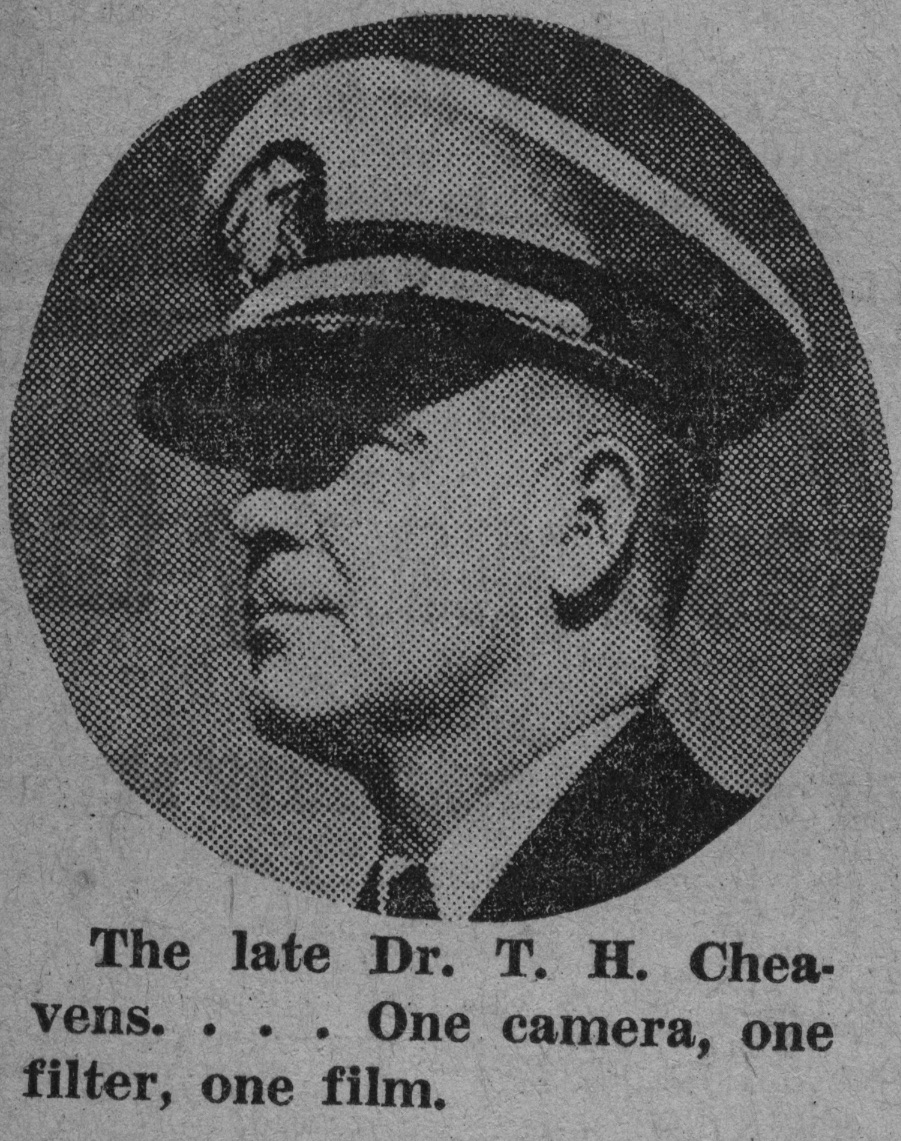

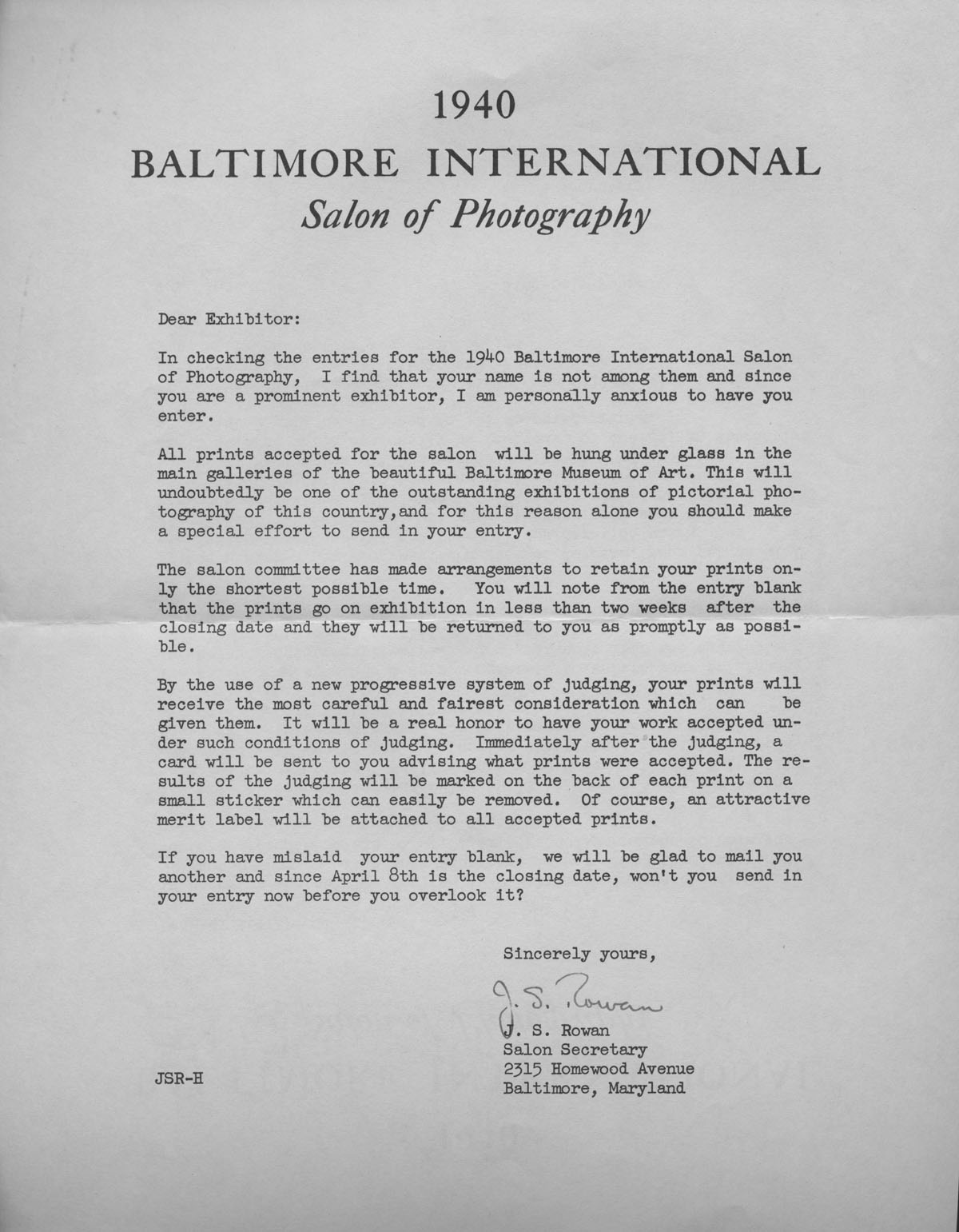

I wished to contribute to Salons, and did so, although I have been led to believe they were a lot of baloney—maybe even a menace or something. I found them a lot of fun. I have tried contests and they are a lot of fun too; as a friend of mine once said, “You always have something to look forward to.”

If I want to tone my prints I do so; this in spite of the fact that I have read effusions to the effect that this wasn’t the thing to do.

I have taken wires out of pictures and I have left them in, and shall continue to exercise my own judgement in this matter. I shall use any size, shape of make of camera I fancy and can afford. If want to make contact prints I shall do so, or [ship/shift?] if it seems more fun. I shall make test strips by the same token; if I want to waste paper it’s my own business since after all it is my paper.

By now I hope everyone gets the general idea. I hope I have succeeded in expelling myself from any school of photography. That is exactly my wish. I know of only one rule in photography so far that seems immutable—“keep your temperatures constant.” I really don’t believe you can break this rule. As far as I know all the others can be broken to advantage on occasions. I even saw an attractive picture which resulted from an accidental double exposure. This was by Mr. Roland Beers and only his modesty will keep him from corroborating this statement.

I think photography is too big for us; we are voicing our opinions as the blind men did in regard to the elephant—by the small portion we have had contact with. What we fail to see is a medium as broad and versatile as any yet known with more functions than a boy scout knife. We can express beauty, ugliness (if we like), texture, movement, rhythm, events, trends, feeling or scientific facts with equal facility.

In this day when the world is half divided between philosophies of freedom and regimentation, I can choose only the former. Photography to me is fun; but the word is inadequate to express how keen the pleasure has been. Therefore I will not allow my freedom to be interfered with—so now, back to the darkroom; I feel better.

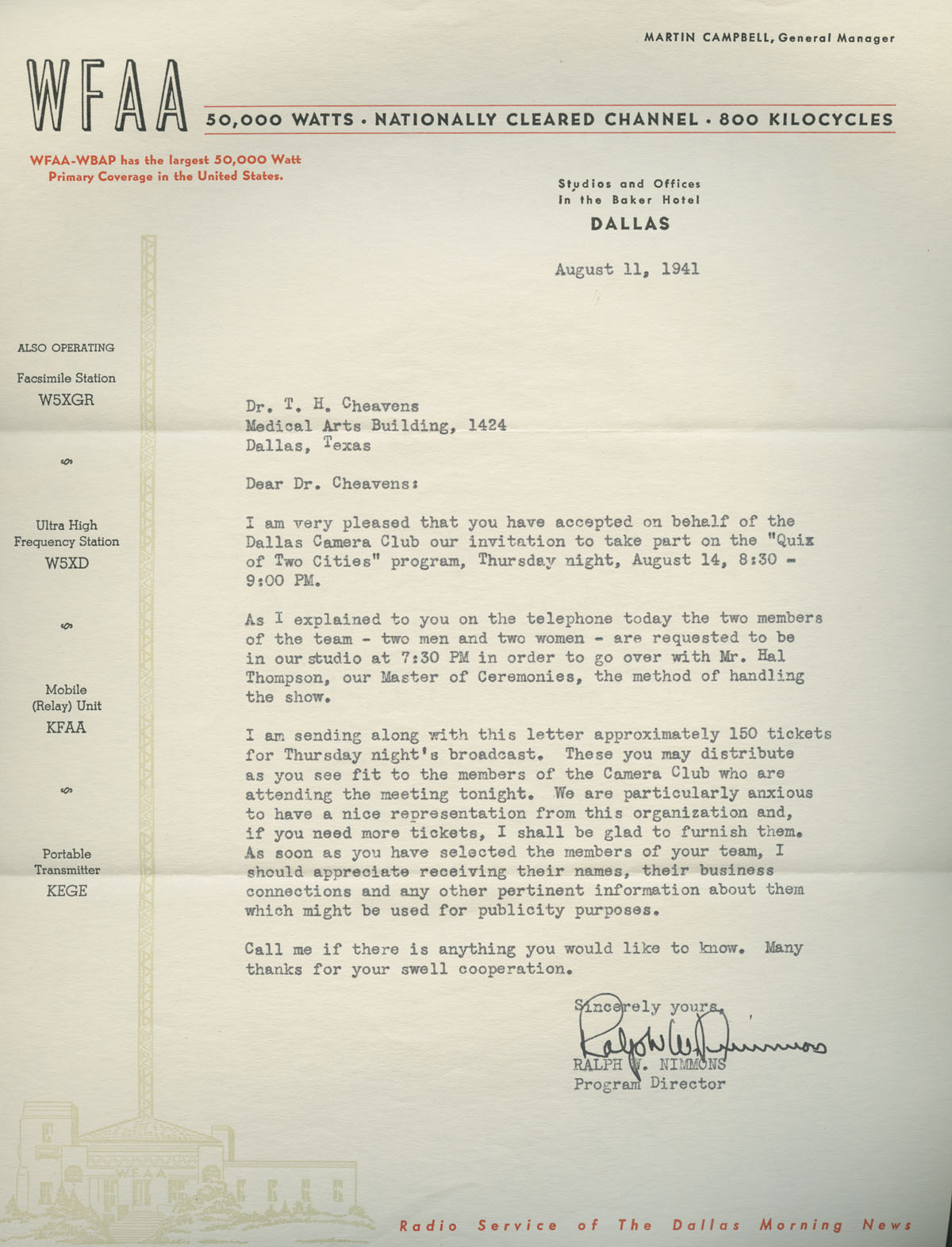

A Psychiatrist Looks At Photography

Camera Craft Magazine, August 1941There must be some interesting and fundamental reasons why photography compels and holds the interest of so many people. A matter so universal cannot be reduced to a sensitive formula, such as one hears, quote "it's the creative instinct," or some such ready-made formula.

As a matter of fact, the professional man sees in photography the exercise of many qualities which are essentially and fundamentally human. Wolfgang Kohler's apes knew how to get an out of reach banana into the cage by the use of the convenient stick, but even a simple box Brownie would merely be something to throw or stand on to these apes. So we may say first of all the camera, with its intricate, precise, ingenious mechanism; film; tanks; enlargers and chemicals appeals to human beings because only human beings could have the intelligence and ingenuity to devise such a hard way to make pictures. It is quite a step from a stone tablet and a chisel. It is even thought by some to be a bit ahead of the red juice of the berry, a chewed stick and some birch bark. So much for the intellectual appeal of photography. Who can resist being charmed by the shiny complexity of photographic equipment? But how about the emotional appeal?

Here we run into a complex array of factors that only a hasty survey as possible. We mentioned a creative instinct: man likes to reproduce. Look at all the little John Does running around the neighborhood and you both see and hear evidence of the fact that humans have an increasing urge to turn off chips from the old block. One is tempted to comment that the more they look like John Doe, the prouder everybody is, including all the aunts and uncles. Photography does this better than any man-made device yet known. The "spittin' image" is still an ideal both in pictures and offspring.

But man goes farther. He seems to enjoy changing the "spittin' image" just enough to leave no doubt that is a 1941 model; definitely not 1940 and so we keep making pictures, and who doubts the pictures are getting better constantly? So the old wagon wheel, babies, dogs and door hinges are still good, provided, of course, that you make them always better.

Man often goes even more deeply into things. Every now and then he turns out something which, to his astonishment, is not only better, but entirely different; no one ever saw anything like it before. Then he is a genius and has a "following"; some don' t like it at all and become very bitter about it; they usually have had no such luck.

Not only does photography give unlimited room for man’s drive to create and reproduce; there is an acquisitive turn in the human race. From the stone age, or before, man has been collecting things: arrow heads, jugs, weapons, bright things like coins. When they slow him down he invents trailers and things to carry them in. Look at the gadgets around any amateur photographer’s home and you will see plentiful, expensive evidence of this drive.

One hears also in Psychiatry of the herd instinct. In the Camera Club you may see evidence of this instinct. Even hobos have their conventions and Coxey’s Armies; the photographer in this respect is no different from the average – he likes to powwow, to have friends, make speeches and get elected to things. I know several fine fellows whose camera is largely useful as a ticket of admission to the Camera Club; no harm done here, they don't win any prizes, but they do have a good time. The comradeship of photographers is a remarkable thing. I once walked into the Chicago Camera Club, an unknown from the wild and woolly Southwest. I was treated as cordially as if I had been introduced by the mayor, or maybe more so. My only credentials were the camera over my shoulder and a certain lingo. This sort of paternalism I have seen in no other situation, unless it is the medical profession. As a force in civilization, it may not be felt at the moment, but in a more fully developed form is capable of breaking many obstructing boundaries and prejudices.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)